- Home

- Carroll David

Ultra

Ultra Read online

For Shawna.

And Mom and Dad.

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Disclaimer

The Starting Line

How I Got My Superpowers

Going, Going, Gone

Finding My Pacer

Nothing Is Impossible

Beware the Chair

Chimney Top

A Different Kind of Sport

The Bonk

The Bandit

Grace Point

In Every Race There Is a Surprise

Sunset at Ratjaw

Do Not Look into the Woods

Come What May

Another Surprise

The Shadow of the Wind

The Shrine

Ollie’s Wise Words

The Kicking of Shins

The Long Shadow

Author’s Note

About the Author

Copyright

NOT FOR PUBLICATION:

This is an unedited transcript of an interview between the thirteen-year-old ultra-marathoner Quinn Scheurmann and Sydney Watson Walters, host of The Sydney Watson Walters Show.

From episode 3261. Broadcast date 19/9/2013.

Property of Sydney Watson Walters Productions, Inc. Not to be copied or excerpted without permission.

THE STARTING LINE

Mile 0

QUINN: I still don’t get why it was such a big deal. All kids like to run. Go to any schoolyard. You’ll see kids playing tag, soccer, capture-the-flag … All those games involve running.

SYDNEY WATSON WALTERS: The difference is, most kids run for 10 or 15 minutes. Not for 24 hours straight, like you.

(Audience laughs)

QUINN: I still don’t think I did anything special. My dad used to say, if you want to run an ultra-marathon, you have to be ultra tough, ultra fast and ultra determined. But I don’t think I’m any of those things. Most of the time I was out there I just felt scared, slow and stupid.

SYDNEY WATSON WALTERS: Take me back to the starting line. That morning in July, before the race started. What was running through your head?

QUINN: I was thinking … I must be out of my mind.

“I can’t believe you’re doing this,” Kneecap said. “Human beings aren’t supposed to run a hundred miles. In a car, yes. On a bike, okay. But on two feet? That’s just stupid. Stooooo-pid!”

Kneecap is my best friend in the world. Which isn’t saying much, I guess, since she’s my only friend.

“I mean, it’s totally whacked!” she went on. “Running all day and all night, through a forest full of wild animals. You heard about the bears, right? Someone spotted a big one on the trail last night.”

Mom overheard this. Her forehead crumpled like a plastic bag. She dug through her purse and handed me the phone. “Take it,” she ordered.

“No way,” I said. “It’s too heavy.”

“Not an option,” Mom said.

I stared at the phone. Mom bought it a decade ago, when phones were as big as toaster ovens. When she just kept hanging on to it, Dad nicknamed it the Albatross.

“You do know I’m running a hundred miles, right?” I said.

“A little extra weight won’t slow you down,” said Mom.

“A little?” I said. “That thing weighs more than our fridge!”

It was 10 minutes before 6, and the sun was starting to come up. Seventy runners were milling up and down the dirt road, holding Styrofoam cups full of coffee and shivering. One woman rotated her arms like pinwheels; another pulled her ankle to her shoulder blade as if her leg were a noodle.

“If you want to run the race, you have to take the phone.” Mom pressed the Albatross into my hand and shot me her death-ray stare.

I squeezed the phone into my fanny pack and struggled to zip it shut.

“Where’s your brother?” Mom asked, glancing around.

I looked down the road. It was covered with shadows.

“There,” said Kneecap.

In the half light, I could see Ollie standing at the edge of a ditch.

“He’s getting his pyjamas wet,” Mom sighed. “Quinn, would you go fish him out of there?”

I sloped down the road. A lineup of runners was standing beside a pair of portable toilets. A skinny lady in a baseball cap waved to me.

I caught up with Ollie. “What’s going on?” I asked.

He was standing beside a creek, staring down at a clump of weeds. “There’s a frog in there somewhere,” he said.

I stared at the ground.

“Spring peeper?” I asked.

“Nope. Leopard frog.”

We went on staring but couldn’t see anything moving except a light breeze blowing through the grass.

“When does the race start?” Ollie asked.

“In ten minutes,” I said, leaning over to stretch out my hamstrings. A wedge of yellow light was creeping over the foothills.

“Too bad Daddy isn’t here to see this,” Ollie said.

A huge raven, the size of a golden retriever, soared over the clearing. It screeched at us — a weird, lonely cry — and the loneliness grabbed me by the throat. My eyes started to burn, but I knew that I wouldn’t cry. Not with Ollie there beside me.

“You’ll be visiting the Shrine, right?” Ollie asked. “You promised Daddy you’d stop there, remember?”

I nodded and poked around inside my fanny pack. The photograph was still there, stowed in one pocket. My salt tablets and energy gels were in there too, plus the Albatross, of course.

“Don’t forget your racing bib,” Ollie said.

“Oh, right,” I said. I knelt down so he could pin the number to my shirt.

“Isn’t thirteen bad luck?” Ollie asked.

“Not for me it isn’t,” I said.

We finally got the number pinned on straight.

Ollie stepped back. “Knock knock,” he said.

“Who’s there?” I asked, rolling my eyes.

“Aardvark.”

“Aardvark who?”

“Aardvark a hundred miles … for one of your smiles!”

A stupid joke. He’d heard it from my dad, the master of stupid knock-knock jokes. Dad had run this race before, and I knew he wished he could be running it again.

The blat of a bullhorn shattered the morning quiet: “ALL RUNNERS TO THE STARTING LINE!”

Electricity shot through my veins. “C’mon, we’ve got to go!” I said. Ollie and I jogged back toward the starting corral. All I could think was: I am about to run 100 miles.

Mom saw us coming and cleared a space in the crowd. She took Ollie’s hand and brushed his bangs out of his eyes. “I thought we agreed you’d stay dry,” she said.

Ollie kicked the road with the toe of his rubber boot. “But I was looking for frogs,” he mumbled.

Kneecap appeared out of nowhere and slung her arm around his shoulder. “You’re a frogaholic, Ollie.”

Ollie giggled and pointed at my racing bib. “And you’re a jogaholic!” he said.

I laughed at that. So did Mom. Kneecap punched me in the shoulder — hard.

“Ouch!” I said. “What was that for?”

“You laughed!” she said. “You actually laughed!”

“So what?” I said. “I laugh all the time.”

“As if!” said Kneecap. “You used to laugh. Lately you’ve been a total fun vampire, sucking the fun out of everything.”

I did?

The bullhorn boomed. “GOOOOD MORRRRRNING, ATHLETES!”

The crowd of runners spun around. Bruce, the race director, was standing beside the gatehouse. He was dressed in a plaid kilt and a black hoodie that said Shin-Kicker 100 across the front. His head was shaved and he had mutton-chop sideburns. A

rainbow-coloured scarf was wrapped around his throat.

“YOU RUNNERS ARE LOOKING STRONG!” he bellowed.

The runners cheered. Bruce raised a hairy arm in the air and then walked backward across the road, kicking a line in the dirt with the heel of his boot. “This is your new best friend,” he announced. “It’s the starting line and the finish line. Two minutes from now you’ll cross this line. And in roughly twenty-four hours, if you’re lucky, you’ll cross it again, only by then you’ll be a totally different person.”

Kneecap punched me again. “You’re really doing this!” she said. “You’re actually going to run a hundred miles!”

I didn’t answer. I was still thinking: fun vampire?

“The thermometer’s headed up to thirty-three degrees,” Bruce went on, “so be sure to drink lots of liquids out there. We’ve got emergency water drops at miles nineteen and fifty-seven, just in case. If anyone gets heatstroke and ruins my race, I swear I’ll feed you to the bears myself.”

“See?” said Kneecap. “I told you there were bears.”

Mom took my arm. “Quinn, are you sure you want to do this?” she said.

Stupid question. “Of course,” I said.

Mom kept brushing Ollie’s bangs with her fingers. “I’m just worried that people will think I’m irresponsible,” she muttered. “You don’t think I’m an irresponsible mother, do you?”

This was bad. She’d already cleared me for takeoff. I couldn’t let her back out now.

“I’ll be fine,” I said firmly. “I’ve got superpowers, remember?”

“I know,” said Mom. “But that won’t help against the bears.”

Kneecap stepped in. “Don’t worry, Mrs. Scheurmann,” she said. “The bears won’t come anywhere near Quinn so long as he keeps singing. You can do that, can’t you, Q-Tip? Sing some of your songs. That’ll scare the bears off for sure.”

“SIXTY SECONDS!” Bruce shouted into the bullhorn.

I clipped on my hydration pack and took a sip from my water bottle. The other runners peeled off their windbreakers and tearaway pants and lobbed them to the side of the trail. I suddenly needed to go to the bathroom, even though I’d gone 15 minutes before.

“Remember,” Bruce said, his voice tinny and electric, “in every race there is a surprise.”

Mom whispered into my ear, “What does that mean?”

“I don’t know,” I said.

“Excuse me!” Mom shouted. “What kind of surprise?”

We never found out, because Bruce began counting: “THIRTY! … TWENTY-NINE! … TWENTY-EIGHT! … TWENTY-SEVEN!”

“Twenty-six! … Twenty-five! … Twenty-four!” the runners chanted.

Kneecap pressed something into my hand. “Take this,” she said.

It was her brand new phone. “I can’t take that,” I said.

“Sure you can,” she said. “It’s got GPS. It could save your life. Plus, it’s lighter than your mom’s piece of junk.”

I looked over at my mom. She was chewing the ends of her hair. This race needed to start fast, before she changed her mind.

“But you love your phone,” I said. “You’ll go into withdrawal without it.”

“It’s only for twenty-four hours,” said Kneecap.

“But —”

“Shut up and take it,” she said. She reached out and grabbed the Albatross out of my pouch and tucked her phone back in its place. “Please don’t get it wet,” she said.

I nodded and tugged the zipper closed.

“TEN! … NINE! … EIGHT!”

I stretched my legs one last time.

“SEVEN! … SIX! … FIVE!”

Took one last sip of water.

“FOUR! … THREE! … TWO!”

Stole one last glance at Mom.

The gun exploded. “GO!”

One hundred miles. 160 kilometres. Half a million strides. Starting NOW.

I took my first step. It would be hours before I reached the first rest stop, and two sunrises before I’d cross the finish line — if I crossed it at all.

“Yaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa!” the runners shouted.

I took a second step. And then a third. People on the sidelines cheered.

I was about to burn 10,000 calories. Sweat 20 litres of water. My heart would beat 1.2 million times.

I took a fourth stride. And then a fifth. And after I had taken a fifth, there was nothing to do but take a sixth. I’d travelled 4 whole metres already! Only 159,996 to go.

I jogged down the trail with the rest of the runners. Ollie ran beside me. “Good luck!” he shouted.

He twirled his pyjama top above his head. My lunatic little brother. My good-luck charm.

I waved back at Mom. Her face was a sinking ship.

“Go for it, buddy!” Kneecap shouted. “Kick some shins!”

HOW I GOT MY SUPERPOWERS

SYDNEY WATSON WALTERS: So let’s discuss this superhero business. In her White House blog, Michelle Obama called you a superhero.

QUINN: That’s a nice way of putting it. Most kids at my school think I’m a super-freak.

SYDNEY WATSON WALTERS: They’re just jealous of what you’ve done.

QUINN: I doubt it. Ultra-marathoning is about as cool as log-rolling. Nobody’s lining up for my autograph, that’s for sure.

SYDNEY WATSON WALTERS: We should explain. For those viewers who may not know, ultra-marathoning is when people run any distance that’s longer than a traditional marathon, which is 26 miles, or 42 kilometres. Is that correct?

QUINN: Exactly.

SYDNEY WATSON WALTERS: And you were running a really long ultra — 100 miles. How do you train for a race like that?

QUINN: I ran for 2 hours almost every day. I’d run to school in the morning and then back home in the afternoon. Tuesday and Thursday nights I also ran my flyer route. And every Saturday I ran to Kendra Station for my piano lesson.

SYDNEY WATSON WALTERS: How many miles were you running every week?

QUINN: A hundred, maybe a hundred and ten. I wore out three pairs of running shoes in four months.

SYDNEY WATSON WALTERS: I’ve heard that your body is different from most people’s.

QUINN: Yeah, my heart is freakishly big. Twenty per cent bigger than other kids my age.

SYDNEY WATSON WALTERS: How does that affect your running?

QUINN: A bigger heart can pump more blood. The more blood your heart pumps, the more oxygen gets delivered to your muscles, and the easier it is to run. So I don’t tire out as fast as other runners. Plus, I have another advantage.

SYDNEY WATSON WALTERS: I’ve heard about this — your body doesn’t produce much lactic acid, right?

QUINN: Exactly. You know how, when you run really hard, your legs start to burn? That’s the lactic acid. It fills up your muscles and slows you down. But my body sucks at making the stuff. So I can run for a really long time without conking out.

SYDNEY WATSON WALTERS: When did you realize that you had these superpowers?

QUINN: A long time ago …

I was eight. Dad was training for a marathon that spring, and every morning he’d get up early for a jog. One day he caught me watching cartoons. “Hey, Quinn, want to come?” he asked.

“No thanks,” I said. Why run when I could sit? That was how I thought back then.

“Come on,” he said. “Quality time with your dad! We never get to hang out, just you and me.”

This was true. Oliver was still a baby then, and between the feedings and diaper changings he was hogging my mom and dad all to himself.

“Come on,” Dad said. “I’m just doing one loop of the Headwaters Trail. You can run it faster than me, I bet.”

I tossed on my gym shorts and my Oilers jersey. I didn’t have any real running shoes then, so I just pulled on my Wheelies. Dad and I crept out the back door without waking Mom or Ollie, and then we crossed the field behind our house and jogged up Appleby Line.

It was a crisp April morning, and the trees were covered

with lime-green buds. The sky was as blue as a swimming pool.

“I’m cold,” I said. “Can I go back for my jacket?”

“You won’t need it,” said Dad. “We’ll be sweating in no time.”

The trailhead appeared at the end of the subdivision. We trotted down the path in single file, skirting the little creek that leads to Watson’s Pond.

“Don’t go too fast,” Dad called out. “Save some energy for later.”

I sprinted ahead, to show him who was boss. No one else was on the trail, and I sang out loudly as I ran.

You got bike spokes in your stomach

And your veins are full of stones

And did you need to fill your ’hood

With all those broken bones?

It was a song by Troutspawn, one of my dad’s favourite bands. Troutspawn was one of my favourite bands too.

The dirt path led up the side of the hill. I charged up the slope until I saw a stripe of orange. I stopped and looked down. Hundreds of caterpillars were crawling around in every direction.

“Woolly bears,” Dad said, pulling up behind me. “Skunks love to eat those guys.”

“Really?” I asked.

“Sure. The skunks roll them over and over on the ground, until they scrape off all the long hairs.”

The caterpillars pulsed slowly along. I imagined the skunks rolling them in the dirt as if they were pizza dough, then chewing them into ribbons of goo. “Not a very nice way to die,” I said.

“That’s Mother Nature for you,” said Dad.

We started running again. The hillside was covered in trilliums and forget-me-nots. The path got steep, and when I stopped and looked behind me, I couldn’t see my dad anymore. I figured he must have stopped to walk.

At the top of the hill, the trail popped out of the woods and crossed a grassy field. A little stone church stood not far away. I jogged over to the graveyard and sat down on a wooden bench to wait for Dad. He appeared a few minutes later. He was gasping for air and his face was bright red. He sat down on the bench, rubbing his knee.

“That’s a tough little hill,” he said.

“I guess so,” I said. I didn’t think it was that tough.

I walked over to the edge of the escarpment. Kneecap calls Tudhope a “flyspeck town,” but it looked sort of pretty from up here. I could see the water tower with the name of our town in block letters, and the empty parking lot where the bus stops six times a week. I could see the marina docks where, in another couple of months, the motor boats would be tied up.

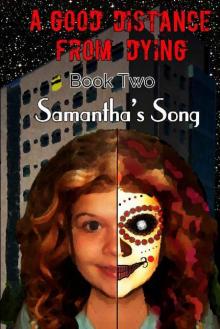

A Good Distance From Dying (Book 2): Samantha's Song

A Good Distance From Dying (Book 2): Samantha's Song Ultra

Ultra